A few days ago, I posted about some chilling COVID statistics[1], and said that each time you get COVID, you and your children ‘roll the dice’ (referring to the relatively high probability of death and/or organ damage/disability).

A friend of mine commented that this was ‘loaded language and emotional rhetoric’, and it came ‘across as an attempt at manipulation or a genuine reflection of fear felt by the author’.

Setting aside the obvious ‘loaded dice’ pun[2], I’d like to interrogate the meaning of ‘rolling the dice’ (and also the use of such rhetorical flourishes in a Health and Safety context).

“Rolling the dice” is generally[2] defined as “…something could have either a good result or a bad result”, or “to take a risk in the hopes of a fortunate result or gain“[3].

Colloquially, I’ve always thought of it in the second sense given by Miriam-Webster: “It’s a roll of the dice whether we succeed or fail.”, meaning that we are not in control of the outcome, and you should be prepared for the high chance of negative outcome.

Of course, ‘high chance’ is defined differently by different people, and in different situations, people having different risk thresholds than each other, and at different times. For example, a 1 in 10 chance of the bottom of your sock becoming wet[4] is very different than a 1 in 10 chance of being hit by a car.

For the sake of argument, let’s compare the above usage of ‘rolling the dice’ with the most popular[5] dice betting[5a] game ‘Craps‘. In Craps, the two most well known[6] sets of odds are ‘Pass’, or ‘will you win this set of rolls’, and winning on the first roll.

‘Pass’ has a win rate very close to 50%[7], perhaps the origin of the term ‘crapshoot’.

Winning on the first roll in Craps requires rolling either a ‘7’ or an ’11′[8], for a total probability of 8/36, or about 22%. Many might think that rolling a 7 is the way to win in Craps (it’s also one way to lose, if your first roll was 4,5,6,8,9,10). Rolling a 7 has a probability of 6/36, or about 17%.

17-22% is within the range of values found in the literature for the prevalence of Long COVID (currently listed as 5-50% by Wikipedia), and is not dissimilar to the 1 in 7.7 (about 13%) deaths in Canada in 2022 attributed to COVID.

One could also argue that ‘a roll of the dice’ is rolling one six-sided die[9], but that just gives us the 1 in 6 or ~17% chance above again. Higher (or lower) order polyhedral dice[10] (or larger numbers of dice) can give us arbitrarily different odds, but let’s stop here.

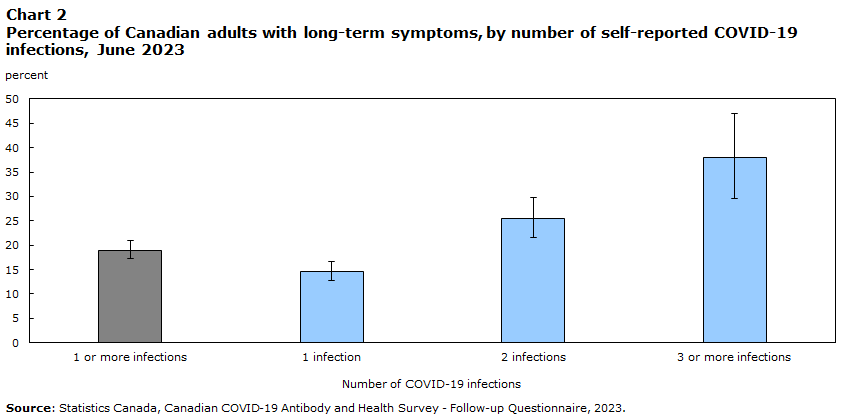

Today, Statscan reported on the prevalence and ‘Experiences of Canadians with long-term symptoms following COVID-19’.

# of inf. % LTS 95% Confidence Interval (lower, upper) 1+ infections 19.0 17.3 20.9 1 infection 14.6 12.8 16.7 2 infections 25.4 21.5 29.7 3+ infections 37.9 29.5 47.0 Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian COVID-19 Antibody and Health Survey - Follow-up Questionnaire, 2023.

This shows that about 14.6% reported long-term symptoms after one infection (about 1 in 7), then of the remaining 85.4%, about one in 8 developed long-term symptoms after a second infection, then of the remaining 74.6%, about one in 6 developed long-term symptoms.[11]

Each of these is pretty close to ‘a roll of the dice’, as we defined above.

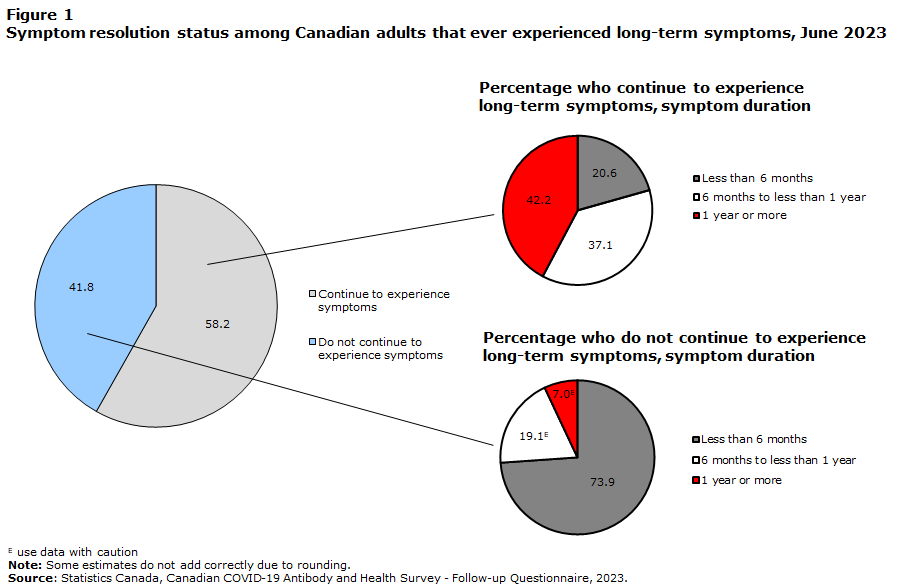

Perhaps more disturbing is that more than half of those who reported long-term symptoms reported no improvement in those symptoms over time:

Also, more than 1 in 5 of those with persistent symptoms (600,000 Canadians) missed days of work or school, missing an average of 24 days each.

Having shown that this is a reasonable use of the phrase ‘roll of the dice’, I also wanted to address the idea of using emotional appeals in public education about health and safety.

A number of years I had the privilege of attending safety training run by Minerva Canada, where a talk was being given by a representative from a car manufacturing company that you’ve heard of. He was talking about their ‘getting to zero’ workplace accidents project, and he mentioned that at some point, after you’ve tried asking people nicely enough times, you have to get the ‘300 lb gorilla to go tell the guy to wear his @#$%ing safety harness’.

That was my sixth and this will be my seventh post talking about the dangers of COVID. At some point, using stronger (but still accurate) language to educate people about the dangers they and their children face due to action or inaction becomes necessary if we actually want to solve the problem.

Thank you for reading, and stay safe out there.

[1] “tl;dr: About 1 in 8 deaths in 2022 in Canada were caused by COVID-19. Organ damage caused by COVID seems to be persistent. Each time you get COVID, you and your children roll the dice again as to whether you die or get Long COVID. Get boosted, mask (with an N95 respirator) when you’re indoors with others. Get COVID as few times as you can, and if you get it, rest up longer than you think you need to. Push for better (HEPA) air filtering and ventilation (more air interchanges per hour).” link to post

[2] In this case, specifically by Miriam-Webster

[3] Idioms Online

[4] Captain Minor Annoyance (abbreviated MI’) is the creation of Ryan George, one of my favourite Youtubers

[5] In North America. Apparently, Craps, and its predecessor ‘Hazard’ are nowhere near as popular in the rest of the world.

[5a] I mention the ‘most popular dice betting game’ partially because most people will have a passing familiarity, I know some of the odds, and those odds are easy to explain. Compare with the games on the ‘top 10 all-time best-seller list‘: Monopoly (3), Clue (5) (uses one six-sided die for movement, but the deduction and knowing your opponents is far more important for gameplay), and Backgammon (8)

[6] I admit, most well known to me, based on learning about Craps during a probability module in high school. There are a large number of ‘standard’ betting options in Craps, but I suspect most people will not have heard of most of them.

[7] Wikipedia says the Craps ‘Pass’ house edge is less than 2%, similar to that of Blackjack, also well-known for have a very slim house edge.

[8] TIL that ’11’ is often called ‘Yo-leven’, to prevent confusion with ‘seven’.

[9] You’d be wrong, as I define ‘die’ as one die, and ‘dice’ as two or more, but many people disagree.

[10] Most common are 4 (tetrahedron, don’t step on these!), 6 (the familiar cube), 8 (octahedron), 10 (not a platonic solid, but a ‘Pentagonal Trapezohedron‘ #til), 12 (dodecahedron), 20 (icosahedron)

[11] Here, I’m assuming that each time a person catches COVID, they either progress into Long COVID, or stay ‘long-term unaffected’. This allows modeling of each subsequent infection independently. With the numbers above, 1st infection has a ~14.6% chance of leading to Long Covid (1 in 6.85), of the remaining 85.4 people, 25.4-14.6=10.8 of them or 10.8/85.4 = 12.6% or 1 in 7.9, then of the remaining 74.6 people, 37.9-25.4=12.5 of them or 12.5/74.6 = 16.8% or one in 5.97. Note that the last number includes those with more than three infections, so one would expect the number for 3 infections to be less than that. Also note that biology is often not linear, and a linear model such as this one may be simplistic, and should only be used for illustrative purposes, no matter how well it fits the curve.