Recently, a couple of friends of mine shared the following meme:

(circled) ‘Is Oppenheimer based on a true story’

‘Is Einstein in Oppenheimer movie?

Why did Cillian Murphy lose weight for Oppenheimer?’

‘Did Cillian Murphy have to lose weight for Oppeneimer?’

(circled) ‘Is the nuke in Openheimer real?’

(circled) ‘Did they drop a real nuke for Oppenheimer?’

On the face of it, it may seem harmless, poking some fun at people who not only know less than you, but who know less than you consider reasonable (or perhaps even ‘possible’!)[1].

However, this laughing at others can lead to contempt, and a reluctance in the willingness of others to ask questions, due to the loss of psychological safety.

So, why might people laugh at those who know less about a topic than they?

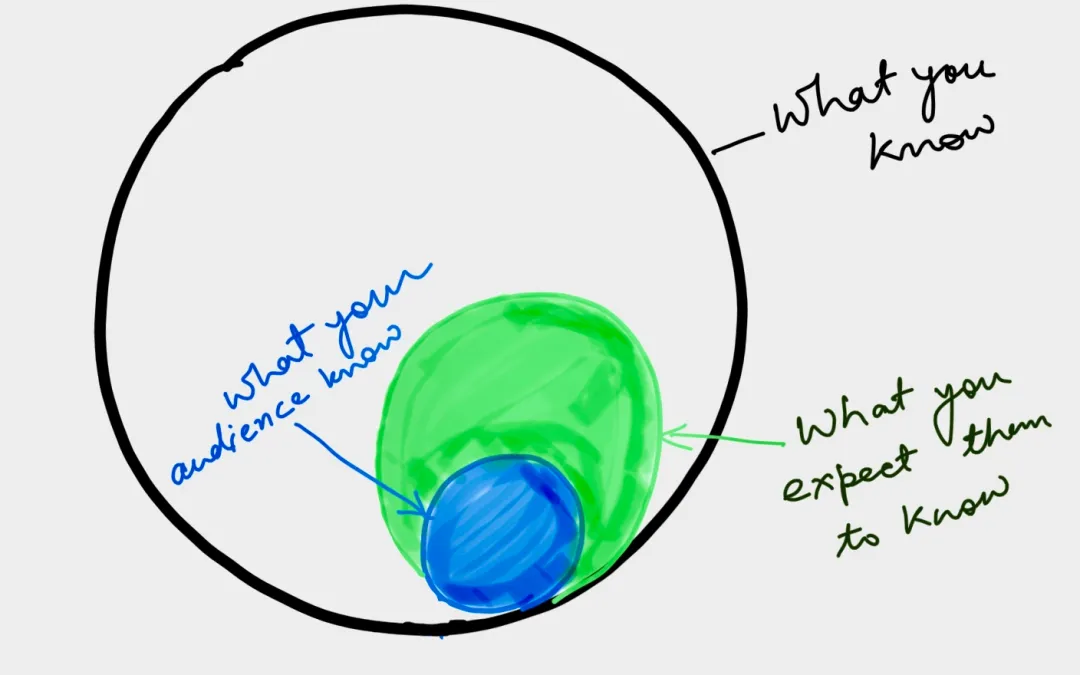

Some describe surprise as a necessary component of laughter. You can be surprised that others know not just less than you know, but even less than you think is possible to know. This cognitive bias causing this surprise is a subset of the ‘Curse of Knowledge‘, perhaps best summed up by this drawing from Rajesh Mathur:

Outer Circle titled ‘What you know’

Smaller circle titled ‘What you expect them to know’

Smallest circle titled ‘What your audience knows’

Sometimes, however, the laughter is not just about surprise, but also comes from a place of insecurity, the desire (conscious or not) to place one’s self above others. This could also be a trauma response, perhaps to experiences with ‘Sealioning‘, where people will repeatedly throw bad-faith questions into a debate or forum instead of engaging with the argument directly.

Another variant of this occurs often in teachers (and oddly enough, IT professionals), where if you’re continually hearing the same question from many different people, it can feel like ‘they just don’t learn'[2], because each year (or semester or day), you get a new person who hasn’t asked that question yet.

So, why might people be asking questions like this?

– They genuinely don’t know: As shown in the diagram above, the variability in knowledge between humans is vast. Even though you know about Oppenheimer because you’ve read multiple books on the subject[3], others might only have a passing knowledge, or even none, despite his pivotal involvement with the start of the Atomic Age.

– They might be mostly sure, but their experience with the thing made them doubt, or they heard a rumor….and the consequence[4] of their assumption being wrong is so large, the ‘importance x likelihood'[5] equation pushes them to ask the question, humans being loss-averse.

– They’re asking a slightly different question: ‘Is Oppenheimer based on a true story’ could mean a lot of different things. There’s a wide range between how much the movie ‘300‘[6] is based on a true story and how much ‘Oppenheimer‘ is. The question could easily be a rephrasing of “how close is the movie ‘Oppenheimer’ to a ‘true story’?”

– They may have difficulties expressing the specific question they want answered: I think it’s worth mentioning that the ability to ask specific targeted questions into a search engine is a (mostly learned) skill, and like all skills, is subject to privilege and ableist gatekeeping. In fact, one could argue that a large part of the uptake of GPT-like software is their ability to answer peoples’ questions when they are not phrased precisely, helping those who are less able to quickly articulate precise thoughts in written form.

– The search engine could be condensing or de-duplicating the wording of questions asked: On a purely technical note, the search engine has a limited amount of space on the page, and it would make sense that they would condense similar questions into perhaps the simplest and clearest version, making it look like people were very commonly asking a simple question.

Thanks for joining me on this wandering journey. I want to learn (and help others learn) to treat others with more kindness, and it’s important to me to deconstruct all of the reasons behind why I (or others) might be doing this. Thanks for reading!

[1] Having done a bunch of teaching, I was aware of the importance of teaching to different styles of learning, and also to different levels of knowledge, but I remember first hearing about this specific subset of this bias relatively recently, probably in a meme, where an expert in a field says ‘how can they not know about this

[2] See also ‘Endless September‘.

[3] Most of my knowledge and understanding of Oppenheimer is from Feynman.

[4] This consequence can be social, such as ‘why didn’t you know about this?’, or personal, such as ‘I don’t want to change the way I think about this unless I have to’, amongst others.

[5] Humans are generally bad at judging the overall expected value of ‘Low-Probability, High-Impact’ events, which is probably why insurance is a thing, although the reduction in distraction/open-loops is probably worth it.

[6] Yes, I know ‘300’ is based on a graphic novel, that’s part of the point I’m trying to make. I’m specifically mentioning 300 because of the large number of known historical inaccuracies and general problematic-ness. There’s also a huge conversation about ‘The Western Canon’ that is out of scope.