If you’ve never read alt.comp.risks, you should do so. In fact, you can read the digest here:

https://catless.ncl.ac.uk/Risks/

If you don’t know what alt.comp.risks is, it is 30 years of all the things that can go wrong with complex systems (especially computers). Anyone who has done a post-mortem or incident report or accident report will familiar (if not happy) reading there. They will probably also notice that the same problems keep happening again and again and again.

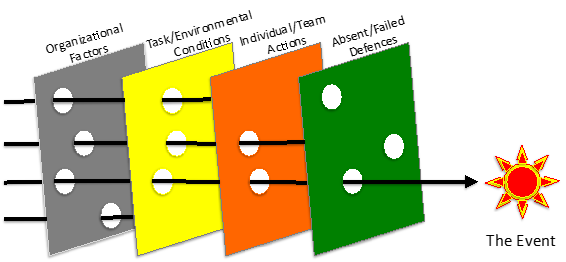

Young Drivers mentioned a study* which said that a typical traffic accident requires four errors on the part of the drivers (two each). In the accident and risk analysis world, this is often referred to as the ‘Swiss Cheese’ model. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swiss_cheese_model

The ‘Swiss Cheese’ model is the idea that adding more layers of checks and protection can help make a system safer, as long as the holes in those layers do not align.

This is a major reason why it is just as important to investigate incidents as it is to investigate accidents. ‘Incidents’ are occasions where something ‘almost went terribly wrong’, where two or more of the ‘Swiss Cheese’ holes aligned, ‘Accidents’ are where all of the ‘Swiss Cheese’ holes aligned, and something terrible actually happened. In the Diagram below**, the ‘Accident’ is the arrow that made it all the way through, all of the other arrows are incidents, which left unchecked, could lead to accidents some day.

Why do we not just spend our time and energy closing those holes in the ‘Swiss Cheese’ (or to making sure they don’t align)? All of that takes money or other resources***. So, given the modern legal system, most organizations balance money and safety in some way, shape, or form. This balance between resource allocation and safety is such an issue that there is an entire regulated profession whose purpose is to properly maintain the balance.

I’m speaking of course of Engineering. The perception of Engineering is perhaps of people building things, or Leah Brahms and Geordi arguing about how to make warp engines go faster, but fundamentally Engineering is about balancing safety with costs.

Probably the most pernicious obstacle to this proper balancing is the dismissal of incidents as unimportant or contained. Any incident which makes its way through 3 of your 4 layers of safety is one mistake away from a disaster, and should be treated accordingly.

*I can’t seem to find it at the moment, but I believe them, as it is consistent with my experience.

**From http://raeda.com.au/?p=115 “The ICAM (Incident Cause Analysis Method) Model Explained

***Often not stated is that spending time on safety-related things is a distraction, both in time and context switching.